What is a Tag: History, Meaning, and Practical Use

What is a tag?

Tagging is a system of marking (or labeling) content, where each element (an article, an image, a post, etc.) is assigned keywords or phrases that describe its content.

In other words, a tag is an identifier or a brief characteristic that allows the material to be associated with a certain topic and makes it easier to find among many others.

Tags are used everywhere in the digital world: from blogs and news websites to social networks, online stores, and of course, stock photography platforms.

For example, an article about cooking recipes may have tags like “food,” “recipe,” “vegetarian dish,” while a photo of a cat could be tagged “cat,” “animal,” “pet.” These labels help users quickly understand the theme of the content and find materials on topics of interest.

Today it’s hard to imagine the internet without tags. On social media, hashtags (tags with the # symbol) unite posts into a common theme; in blogs, tags group related articles; and in stock photography libraries, tags are the main tool for searching specific images.

Why has tagging become so important? The reason is that information on the web is growing at an explosive pace, and classifying content is the key to making something easy to find in this ocean of data. Tags act as “beacons” or navigational markers, indicating what the material is about and allowing users to filter and group content.

As experts point out, a properly organized tagging system expands search capabilities and improves user experience.

In this article, we will explore what is tags, how tags appeared and evolved, why they have become an integral part of the modern internet, and also highlight best practices for using them — from social hashtags to professional image attribution on stock photography platforms.

Tagging as a Process

So, we’ve already established that a tag is a label (a keyword or phrase) assigned to an object (content) for its classification and description. A tag briefly conveys the essence of the material and acts as a pointer when searching for the right information. The set of tags helps structure data: each tag groups all objects marked with it into a kind of virtual category.

For example, if several products in an online store are tagged with “smartphone,” clicking on this tag will show the buyer a list of all products related to mobile devices. Thus, tags allow content to be classified not hierarchically, but across multiple overlapping criteria, creating a flexible multidimensional system for organizing data.

Tagging is the process of assigning tags (labels) to content elements. In practice, it’s the manual or automatic labeling of material with keywords that reflect its topic or characteristics.

The purpose of tagging is to simplify the subsequent search and identification of needed objects using these words.

Tagging can be done either by the content creator or by users themselves. For example, a photographer uploading their work to stock platforms enters the tags manually, while on some platforms (forums, social catalogs), readers or community members can add them. Tags are usually displayed next to or beneath the content (on an article, post, or video page), or grouped in a list or cloud of popular tags on the site.

It is important not to confuse content tags with HTML tags.

In web development, HTML tags are markup elements (such as <h1>, <p>, <div>) that tell the browser how to display the content. In our context, we are talking about descriptive tags (content labels) that outline the topic or attributes of the material and are used for navigation and search—not for page formatting.

These user-generated tags are often stored as part of the content’s metadata. For example, a blog entry may contain HTML markup for headings and paragraphs but also be tagged with “business,” “startup,” and so on for classification purposes.

The principle of tagging is simple: assign several relevant keywords to the content, and then any user interested in the topic can, with a single click, see a list of similar materials under the same tag.

Unlike rigid categorization (categories), tagging allows the same object to belong to several groups at once. For instance, a rug in an online store may simultaneously carry the tags “rug,” “home accessories,” and “cozy living,” and it will be accessible through all those thematic search sections.

This is a multidimensional way of organizing information, closer to the way people actually think (an object can have several attributes at once). It is precisely this flexibility that has made tagging such a popular method for classifying content.

How Tags Appeared: A Brief History

Although tags became widely discussed relatively recently (with the rise of social networks and Web 2.0), the very idea of assigning keywords to objects arose long before that. Even in the early digital era, there was the concept of “keywording” — assigning a document or file several keywords to make it easier to search.

For example, when organizing old newspapers, librarians could add thematic labels to issues. If a newspaper from 1885 never once contained the phrase “Wild West” but was dedicated to life in what is now North Dakota, a librarian could add the keyword “Old West” — and then a researcher looking for materials on the “Wild West” would still find that newspaper.

This shows that keywords as metadata have long been used to improve information discovery, even in cases where the sought-after words are not directly present in the text.

In the early web of the 1990s, meta tags were used (for example, <meta name="keywords" content="..."> in the HTML code of a page), where webmasters entered a list of keywords about the content of the site. However, search engines soon stopped trusting meta tags: the temptation was too great for unscrupulous webmasters to stuff them with popular words like “sex” or a celebrity’s name, which had nothing to do with the actual content of the page.

So search engines (such as Google) practically ignored meta keywords — and if the history of tags had ended with the author’s indication of keywords for SEO, tagging might have been forgotten.

But in the mid-2000s, a qualitative leap occurred: tags “went public.” Instead of only content authors or webmasters assigning labels “from above,” ordinary users gained the ability to tag information themselves. This approach was called folksonomy (from folk — people and taxonomy — classification) — in other words, “people’s classification” of content using freely chosen tags.

The term Folksonomy was first introduced by American analyst Thomas Vander Wal in 2004, when a boom of user tagging on new web services was beginning to take shape.

The first widely known platforms to introduce free tagging were Web 2.0 social services. In 2003, a service appeared — an online bookmark manager — where users could save links and label them with their own tags for easy sorting and searching.

Shortly after, in 2004, the photo community Flickr launched, allowing users to upload photographs and provide them with descriptive tags. On Flickr, by clicking on the tag “cat,” one could see all public photos of cats uploaded by different people. This was an entirely new approach to organizing information — bottom-up, from user associations, rather than from a predefined structure.

It is worth noting that this approach proved viable and attractive. By 2005, the total number of users of this service reached hundreds of thousands. In mid-2005, Flickr had about 375,000 active users.

For that time, these were significant numbers, showing the demand for this new method of navigation. Major IT companies also took note of the trend: in spring 2005, Yahoo! acquired Flickr, and analysts pointed out that one of the reasons for the purchase was precisely Flickr’s technology and experience with user tagging.

Yahoo already had its own photo service at that time, but the interest in the tagging system itself showed that tags were being seen as a valuable asset and tool for improving user experience.

Not surprisingly, media expert David Weinberger, writing about new media in 2005, predicted: “Tagging will undoubtedly become mainstream and will have an impact far beyond mere convenience.”

Gradually, tagging spread everywhere. Popular blogging platforms (WordPress, Blogger, etc.) by the mid-2000s had already introduced support for post tags alongside categories. In 2004, the launch of Google’s Gmail email service also demonstrated the power of the tagging idea: Gmail abandoned traditional folders for emails in favor of “labels,” allowing users to assign multiple tags to a single email and then filter messages by those labels.

This approach gave more flexibility, since an email about a project in Spain could simultaneously be labeled “Project X” and “Spain,” and would appear in both thematic lists, instead of being confined to a single folder. At first, some users found the absence of nested folders unusual, but the concept that “an email can exist in several folders at once” quickly caught on. In fact, Gmail popularized the idea that “labels are virtual folders,” and this principle of information organization proved far more convenient than rigid hierarchy.

In the second half of the 2000s, tags became a mass phenomenon. It is generally accepted that 2007 marked the arrival of tags (more precisely, hashtags) in the global social sphere — and since then, that year has sometimes been called “the moment when tags became part of pop culture.” This happened thanks to Twitter — but we will talk more about hashtags separately.

It is enough to note here that by the end of the 2000s, the mechanics of tagging had been implemented in one way or another on most content platforms: on forums and news sites “tag clouds” with lists of popular topics appeared; on Q&A sites (such as Stack Overflow), tags became the main way to classify questions by topic; in music players and libraries, ID3 tags were used to store information about songs (artist, album, genre); in project management and note-taking systems (such as Evernote and Trello), user tags were introduced to flexibly mark tasks and notes.

Even operating systems adopted the idea: for example, macOS since 2013 has allowed users to put color-coded tags on files, and Windows 10 has supported tags in file properties (for certain types, such as photos). All this indicated that tagging had become a universal tool for organizing data.

Nowadays, when there is too much content to rely solely on hierarchical catalogs, tags have become a lifeline. As one commentator vividly put it, the traditional organization of information through folders and categories is “order imposed from above on the content,” while tagging is “joyful chaos reflecting actual use” (since every user can tag an object in their own way).

Types of Tags and Examples of Use

Tags, in the modern sense, can take different forms depending on context. Let’s look at the main areas of tagging application and how tags appear and function in these domains.

Tags on Websites and Blogs (Content Labels)

On content-driven websites (news, informational sites, blogs), tags usually act as thematic keywords that help group publications. The difference between tags and traditional categories (sections) lies in the fact that categories form a hierarchy, while tags do not. Categories (site sections) are usually few in number and cover a broad set of topics, while tags are added more freely and reflect specific themes mentioned in the material, even narrow ones.

Practice shows that on websites with a large volume of content it is useful to have both systems: categories for the main thematic sections, and tags for cross-classification according to more specific features.

For example, in an online store, categories might be “Smartphones” or “Televisions,” while tags could be “red,” “sale,” or “4K,” enabling users to filter products across categories.

If “iPhone” is a category (a brand, a popular product), a tag could be something like “black smartphones” for grouping by color or “neural network” if such a feature is used in the smartphone (for example, to enhance photos). Tags make it possible to create pages that display content by any combination of properties, even if that combination is not represented in the section tree.

Usually, on article pages, tags appear as a list at the bottom or side, and by clicking on a tag, the user goes to a tag page — a list of all materials with that label. Properly managed, these tag pages can bring additional search traffic, as they allow the site to cover more long-tail queries (more specific searches) and add new entry points from search engines.

SEO specialists note that well-designed tag pages can increase site traffic: you can add additional text with a description of the topic, configure meta tags like Title and Description, improve internal linking — in short, make them fully-fledged landing pages for search.

However, it is important not to overdo it: creating meaningless tag pages (“garbage”) without real value is not recommended, as they only clutter the site and can harm rankings.

The optimal scenario is when each tag represents a truly relevant topic, uniting at least several materials, and the tag page provides added value (for example, aggregating news on a narrow subject that would otherwise be scattered across different categories).

On websites and forums, tags can be predefined or free-form. In some communities, administrators set a fixed list of tags (a controlled vocabulary) from which authors select appropriate ones — this helps avoid duplicates and inconsistencies in spelling.

In other cases, users can create any new tags they want. Both approaches have advantages: free tagging reflects natural language and emerging topics, while controlled vocabularies maintain order and reduce chaos. On some professional websites, a hybrid model is used: moderators can edit or remove tags if they see typos or irrelevant labels, while users can only propose their own options.

Tags in Social Networks: The Power of Hashtags

One of the most famous varieties of tags is the hashtag — words or phrases beginning with the pound sign (#). Today, hashtags are most strongly associated with social networks (Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, VKontakte, and others), where they serve to group posts by topics and trends. Interestingly, long before Twitter, the # symbol was used in a similar way in IRC networks — where global discussion channels began with a hashtag. However, it was Twitter in 2007 that turned the hashtag into part of mainstream internet culture.

The first hashtag on Twitter appeared thanks to user Chris Messina, who on August 23, 2007, published a historic tweet: “What do you think about using # for groups?” — thus proposing the idea of a marker for grouping tweets. Essentially, Messina was looking for a way to improve navigation in the then-new social network, inspired by the experience of IRC channels.

The idea was initially met with skepticism (not everyone believed people would use hashtags), but just a couple of months later, life gave hashtags a serious test.

In the fall of 2007, large wildfires broke out in California, and hashtags suddenly came into practical use: blogger Nate Ritter, covering the events, tagged his tweets with #sandiegofire (after the city of San Diego). Others quickly joined in — and so the hashtag became a tool for real-time news sharing during an emergency, allowing people to filter their feeds for all fire-related updates.

This case vividly demonstrated the power of the new tool: any word with # turned into a clickable link that grouped all related messages. By 2009, Twitter officially supported hashtags (with links automatically generated for tag searches), and by 2010, the service’s homepage featured a “trending topics” block — the most popular hashtags of the moment.

In just a couple of years, hashtags became an inseparable part of internet vocabulary. If in 2007 the most popular hashtag was used only about 9,000 times, ten years later, social media users were publishing around 125 million hashtags daily.

Such growth — thousands of times over — reflects the global spread of this culture. Today, the # sign is even called a “symbol of the digital era,” since it has enabled entire social movements and flash mobs. For example, the hashtag #MeToo became the emblem of a massive social campaign, uniting millions of people worldwide around the issue of sexual violence. In such cases, a hashtag serves not just for navigation but also as a rallying banner: by posting #MeToo, people express solidarity with the idea and make their voices part of a collective chorus.

Mechanically, a hashtag differs little from a regular tag, except that it is written as one continuous word (spaces are not allowed, underscores may be used instead). Social networks usually highlight hashtags with color or bold text to make their clickability clear.

An important feature: anyone can create a new hashtag, and no central authority controls their use. This is both a strength and a weakness. On the one hand, this freedom allows a hashtag born from a local joke or obscure word to suddenly become a global trend if enough people adopt it — meaning hashtags in social networks can become viral “folk” labels.

On the other hand, a hashtag has no “owner” and no strict definition, so different people may use the same hashtag in different ways, or one and the same topic may split across several variations of spelling.

For example, when discussing a game, some users might use #BigGame, while others use #Big_Game — and the audience could potentially split into two streams. Still, popular social networks have mechanisms that partly mitigate this problem: trending topic displays and algorithms capable of recognizing related hashtags.

Today, each major platform has its own nuances in hashtag usage. For example, Instagram allows up to 30 hashtags under one post and even lets users follow hashtags (since 2017), so new posts with that label appear in their feed.

On Instagram, hashtags are a key tool for content promotion: users often search through them for interesting photos, while brands and bloggers carefully select popular tags to maximize reach. Twitter, on the other hand, recommends no more than 1–2 hashtags per tweet, valuing brevity and precision — so it is not common practice there to “dump a dozen hashtags” like on Instagram.

YouTube allows creators to add hashtags to video descriptions, and viewers can click on them to find more videos on the same topic; hashtags also appear above the video title if added. TikTok largely follows Instagram’s path — with countless challenges built around unique hashtags, and users encouraged to participate using the trending tags of the day.

Thus, tags in social networks have become a social phenomenon, greatly expanding communication possibilities. They not only make navigating content easier but also create a sense of participation in a shared cause: by using a popular hashtag, a user symbolically joins a collective conversation on the chosen topic.

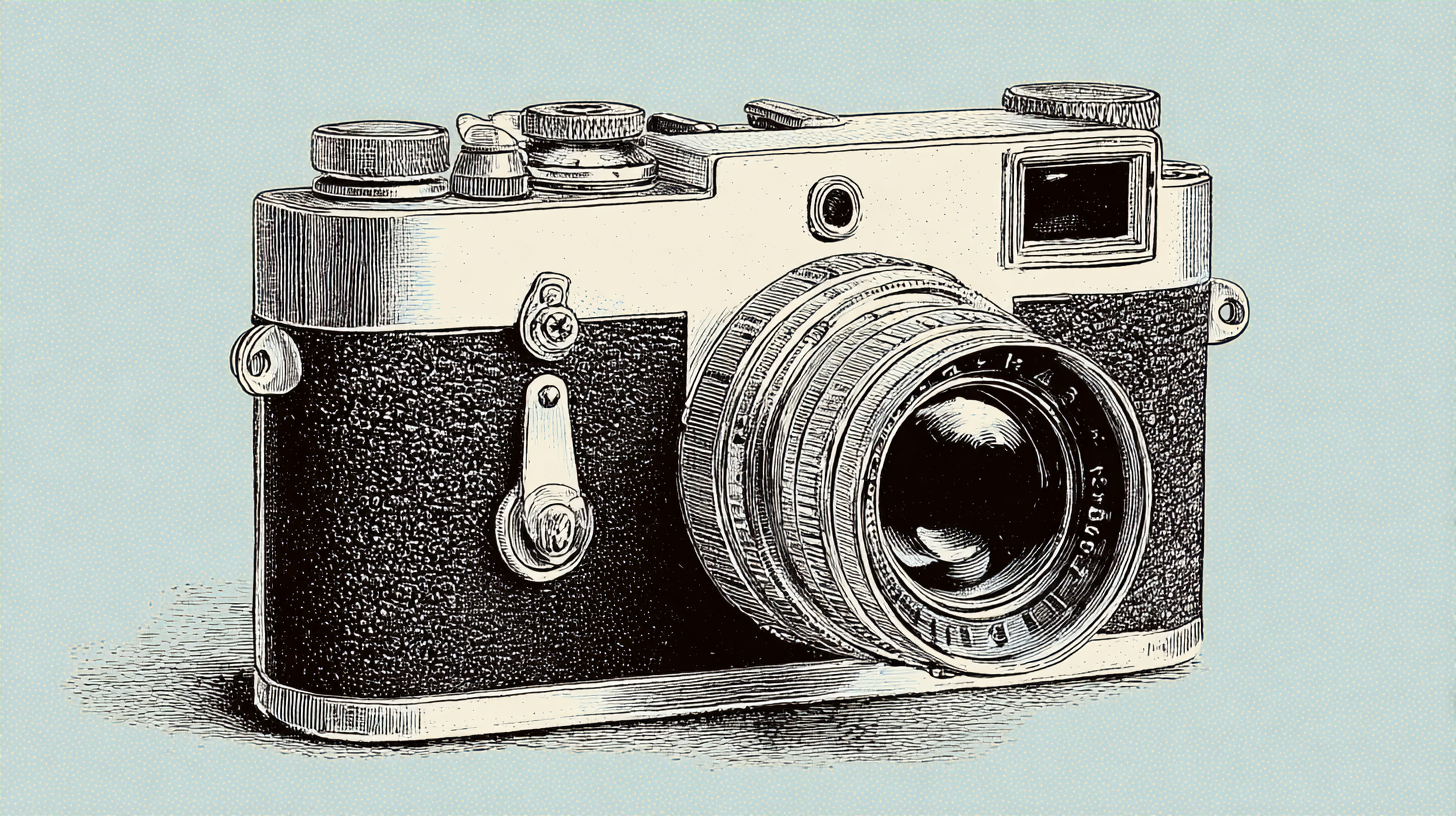

Tagging (Keywords) on Stock Photography Platforms

It’s worth taking a closer look at tags in the context of images and photos, especially on stock photography platforms – the classic example of how critically important tags are. Stock sites such as Shutterstock, iStock, Adobe Stock, Freepik, and others are where photographers and illustrators sell licenses for their work.

Each contributor uploads an image and assigns a set of attributes: a title, description, and keywords (tags). It’s through these keywords that buyers search for the right content. In other words, keywords on stock sites are the main “salesperson” for your work: if they’re missing or poorly chosen, nobody will ever find your image. With millions of files on every stock platform, your chances of being discovered without good tagging are close to zero.

That’s why professional stock contributors pay enormous attention to keywording. Usually, a stock site allows you to assign up to ~50 keywords per image, and it’s recommended to use as many as possible. Shutterstock suggests 25–50, while Freepik allows up to 50 but advises focusing on 15–20 of the most relevant ones.

The idea is to create a complete but high-quality list of keywords describing the image from every meaningful angle. Here are some best practices, based on the guidelines of the leading stock platforms:

-

Use specific and precise tags. The more accurately your tags reflect the content, the better the results. Don’t stick only to generic words – highlight the main subjects and concepts. For example, a photo of a young woman reading in the park can go beyond “woman,” “book,” and “park,” and include “student,” “studying outdoors,” “literature,” “summer,” etc.

-

Think like a buyer. Shutterstock recommends asking yourself: “What search queries would a buyer use?” For instance, instead of “woman with a book,” a buyer might type “student preparing for an exam.” That means adding conceptual keywords like “education” or “exam.”

-

Use keyword phrases. If a concept is naturally expressed with two or more words, add it as a single phrase – e.g., “green apple” rather than separate “green” and “apple.” Search engines on stock sites usually prioritize word order.

-

Tag order matters. Some sites prioritize keywords at the beginning of the list (Adobe Stock advises putting the most important first). Others, like Shutterstock, sort them alphabetically, but many contributors still arrange them by significance.

-

Only relevant keywords. Don’t add unrelated words “just in case.” Both Shutterstock and Adobe Stock warn that irrelevant keywords harm sales by showing your content to the wrong audience.

-

Avoid duplication. Don’t repeat words in different forms – most platforms treat that as keyword spam. One form is enough; plurals and variations are usually recognized automatically.

-

Describe people and objects in detail. For photos with people, specify gender, age, and ethnicity. For example, instead of “person,” use “man, 30 years old, Caucasian, brunette.” This increases discoverability for targeted searches like “30-year-old Caucasian man.”

-

Add conceptual keywords. Beyond the visible objects, think of abstract concepts or emotions. A handshake image can also include “partnership,” “trust,” and “success.” Such tags help buyers looking for ideas, not just objects.

This process directly impacts commercial success. Many professionals dedicate a separate stage of work to keywording – sometimes it takes as much time as shooting or illustration itself.

Some contributors delegate keywording to assistants or use special keywording tools, which can suggest popular tags by analyzing similar files.

In recent years, AI-assisted tagging has become standard. When uploading an image, the system may generate a dozen keywords automatically, and the contributor only has to refine and add missing ones. For example, on TagWithAI, you can upload an image and get accurate metadata in just 5 seconds per file.

Interestingly, both over-tagging and under-tagging are harmful. For example, if too many unrelated files are tagged with “suitcase,” a buyer searching for suitcase images will be frustrated by irrelevant results. This “keyword spam” undermines user trust and platforms often punish it. Some, like IStock, use controlled vocabularies or ban contributors for excessive spamming.

On the other hand, too few tags are equally bad – poorly tagged images risk being buried forever and never discovered.

In short, keywording on stock sites works much like SEO for images. Strong keywords improve visibility; weak ones make your work invisible. This principle applies to all web content, but on stock platforms it’s especially direct and measurable – in downloads and sales. That’s why stock contributors treat tagging as one of the most crucial parts of their workflow.

Tags in Online Stores

Tagging has long become an essential tool in the world of e-commerce. Unlike social media or stock platforms, where tags mostly help users discover content, in online stores tags serve multiple functions at once.

Tags allow you to group products by specific attributes: “summer collection,” “office wear,” “discounts,” “eco-friendly materials.”

Unlike rigid categories (for example, “shoes → sneakers”), tags are more flexible: a single product can belong to multiple groups at the same time. This makes search easier and filtering more intuitive.

Many CMS platforms (such as Shopify, WooCommerce, Magento) let you use tags as part of URLs or metadata. When used correctly, tags can help a store rank for long-tail and mid-tail queries like “white leather sneakers” or “16-inch laptop backpack.”

However, excessive duplication of tags can cause SEO issues (page cannibalization, thin content).

That’s why SEO specialists recommend carefully planning a tag strategy.

In recommendation systems, tags help connect user behavior with products. For instance, if a customer searches for “yoga clothing,” the system can display products tagged with “sports,” “yoga,” “stretch fabric.” This improves conversions, because shoppers quickly find what matches their intent.

Different Approaches to Tagging Across Marketplaces

Etsy: This handmade-focused platform relies heavily on tags, and the right choice of keywords directly impacts sales.

Amazon: While “tags” in the classic sense don’t exist there, sellers use backend keywords (hidden search terms) — which essentially function as tags for the internal search system.

Shopify Stores: Many store owners note that using tags as “smart collections” helps automate storefronts — for example, “all discounted products” or “all green-colored items.”

Automated product tagging powered by computer vision and NLP is already being actively implemented. For instance, Shopify applies AI algorithms to recognize clothing color, shape, and style. This reduces the workload for store owners and keeps catalogs more structured.

Looking ahead, tags are likely to shift away from manual entry and move entirely toward semantic product descriptions generated by AI.

The Growing Role of Artificial Intelligence in Tagging

The sheer volume of content on the internet and in corporate archives today makes manual tagging simply impossible. That’s where automation and artificial intelligence (AI) come in. Modern content management systems (DAM, CMS, and others) are increasingly using algorithms for auto-tagging.

Machine learning can analyze file contents — text, images, video — and extract likely keywords. For example, computer vision services can detect that a photo contains “people,” “car,” and “building,” and automatically suggest those words as tags. This saves enormous amounts of time when working with large image archives.

Major companies managing media libraries are already adopting such solutions. This not only speeds up the annotation process but also unlocks new search possibilities — for example, filtering by body type or skin tone if AI has detected them.

Examples of AI-driven tagging include:

-

Face recognition. Models can identify people in photographs. Once you label a face (in DAM software or even in Google Photos), the system will automatically recognize that person across the archive and assign the tag with their name. In seconds, you can compile all images featuring a particular employee or celebrity.

-

Emotion and attribute detection. Neural networks can interpret facial expressions (smiling, sad), approximate age, and gender. All of this turns into metadata. For instance, AI might automatically add tags like “woman, 40–50 years old, sad” to an image.

-

Object auto-tagging. Perhaps the most popular use case: upload a picture, and the neural network lists what it sees in the form of tags.

-

Safety and content filters. AI tagging can also flag unwanted elements — tagging content as “violence,” “18+,” or “extremism,” so the system knows how to handle it (for instance, blocking it for younger audiences).

Automation is especially crucial at scale. Imagine a company with 20 years of accumulated photo and video assets. Tagging that entire archive manually would take thousands of hours. A neural network, however, can analyze thousands of files overnight — with some margin of error.

In DAM practice, a hybrid approach is common: bulk content is run through AI for preliminary tagging, then results are refined and enriched with specific business-related labels by humans.

So does AI make manual tagging obsolete? Not quite — the trend is more about symbiosis. AI is excellent at generating straightforward descriptive tags (“tree,” “smiling person”), but higher-level meaning and business context often remain out of reach. For example, an AI might not know that a logo belongs to a key brand requiring special tagging, or that an image relates to a specific company project. That’s why humans remain in the loop, especially where domain knowledge is needed. Meanwhile, the repetitive work — describing colors, objects, and surroundings — is increasingly automated.

In short: AI doesn’t eliminate tagging, it makes it more powerful and scalable. Machines handle routine content-based labeling, while humans provide fine-tuned context and abstract concepts. The result is richer metadata, and therefore better navigation and search.

Best Practices for Effective Tagging

After everything we’ve discussed, the key question is: how do you organize tagging so that you maximize the benefits while minimizing the downsides? Below we’ve put together essential best practices — useful for website owners, content creators, and even active users helping to tag content.

Think from a search perspective. The main purpose of tags is to help people find content. When coming up with a tag, ask yourself: “What words would someone type in if they were looking for this?” Use words that genuinely reflect the topic. Avoid internal jargon unless it’s widely recognized.

Use enough tags, but don’t overdo it. The ideal number depends on the platform, but the rule of thumb is to cover all main aspects without drowning in secondary ones. For example, 10–15 tags for an article is fine; 2 tags are usually too few (missing context), while 50 can be overkill (too much noise). On stock photo sites, the sweet spot is around 30–50 (very specific), while for blogs 5–10 is usually enough. The key is that each tag should be meaningful. If you’re adding a tag just “to have one” — better skip it.

Stick to relevance. No “off-topic” tags! This is the golden rule. Even if you’re tempted to reach a broader audience, irrelevant tags do more harm than good. Search algorithms notice this (and may even penalize it), and users themselves can react negatively (reports, spam flags, or just irritation).

Don’t duplicate or repeat. There’s no need to add multiple grammatical forms of the same word. Search engines usually understand plurals and inflections. For example, “car” and “cars” are essentially duplicates; one is enough. Exceptions exist only if the different forms carry different meanings (e.g., “python” the language vs. “pythonic” code style).

Choose a consistent style. If it’s your website or project, align your tag vocabulary. Decide whether you’ll use “tech” or “technology,” “movies” or “films.” If you have a team, create a mini tag guide. This avoids chaos. Regularly audit your tags: merge duplicates (“Startup” vs. “Startups”), and remove weak, one-off tags.

Leverage suggestions and existing tags. If the platform shows autocomplete options, pick from them when appropriate. It’s better to join an existing tag than to create a near-duplicate. This consolidates content and helps users. For example, on forums, always check available tags before inventing a new one.

Mix broad and narrow tags. For example, a post about a rocket launch can have specific tags (“SpaceX,” “Falcon 9”) as well as broader ones (“space,” “rocketry”). The narrow tags help niche readers, while broader ones attract general interest. Just don’t use only broad tags — “science” alone won’t do much without specifics.

Avoid hashtag clutter. On social media, don’t turn your text into a wall of hashtags (#I #am #walking #outside). It looks spammy and unreadable. A good rule: no more than 1–3 hashtags in the main text; if you need more, list them separately (as people often do on Instagram: text + comment with extra tags).

Use templates and batch tagging when appropriate. If you’re publishing a series (say, 10 WooCommerce tutorials), give them all the same series tag (“WooCommerce_tutorial”). This helps users easily access the full set.

Optimize for SEO. If you run a website, tag pages should be well structured: unique titles, meta descriptions, and possibly an intro paragraph. That way, they’ll rank in search engines for long-tail queries and provide value to visitors. Don’t create thousands of thin tag pages — better fewer, high-quality ones with useful content.

Mind context and tone (for social tags). If you join trending hashtags or campaigns, understand the context first. Brands have been burned by using a hashtag without realizing it had a negative meaning. Always check what others are posting under a tag before jumping in.

Update tags when needed. Content lives a long time, and its metadata can be updated. If a new, more accurate tag emerges, add it. Or remove tags that no longer fit. In blogs this is easy, while in forums moderators usually handle it.

In short, think of a tag as a promise to your user. When someone clicks a tag, they expect to see relevant content — or at least understand why your post is tagged that way. If you make your tags truly reflective of the content, the tagging system will work for you, not against you.

Hopefully, this article answered the question “What is a tag?” We’ve tried to analyze the phenomenon from different angles and show that a tag is not just a word or label, but a universal tool for structuring information, navigation, promotion, and discovery.

Leave a Reply

Copyright © 2025 TagWithAi

No comments yet.