Microstock, Midstock, and Macrostock: Three Steps in the World of Stock Photography

If you’ve ever uploaded your shots to stock photography platforms, you’ve probably come across the word microstock. It has firmly settled into the vocabulary of photographers, designers, and illustrators.

For me, back in 2013, that word sounded like a password to a whole new reality. At the time, I was still working as a lawyer, but I was searching for a creative outlet where I could express myself as a photography enthusiast.

On top of that, I had already read plenty of stories about people making good money from it. What inspired me most was that you didn’t have to hunt for clients — you simply take your photos, sign up on a platform, and by the next day someone on the other side of the world might buy them.

It felt like a breath of freedom, like all the barriers had fallen away.

Microstock: A Ticket into the World of Sales

Microstock is like a giant supermarket for visual content. You’ll find everything there — from perfectly staged studio shots to simple but eye-catching phone photos. And every file has the chance to find its buyer.

The prices are tiny — from just a few cents to a couple (sometimes even up to ten) dollars per download. But here’s the trick: you sell cheap, but you sell often. Microstock thrives on volume — the more work you upload, the higher the chances that every day a little something will land in your account.

I remember the first time I saw a few dollars appear overnight from my images — I knew right then I was going to stick with this.

Of course, there’s another side to it. The competition is massive — millions of contributors and billions of files. To break through, you need not only to shoot (or generate with AI) at a high standard but also to understand exactly what is in demand right now. Sometimes you have to set aside creative ambitions and produce content “for the client,” not just for yourself.

But there’s a special kind of joy when you create something that meets market demand and you’re genuinely thrilled with the result. That happened recently with a video series I generated in MidJourney (I uploaded this clip as a GIF so that it would not take up too much space on the server, so the quality is not the best. My apologies):

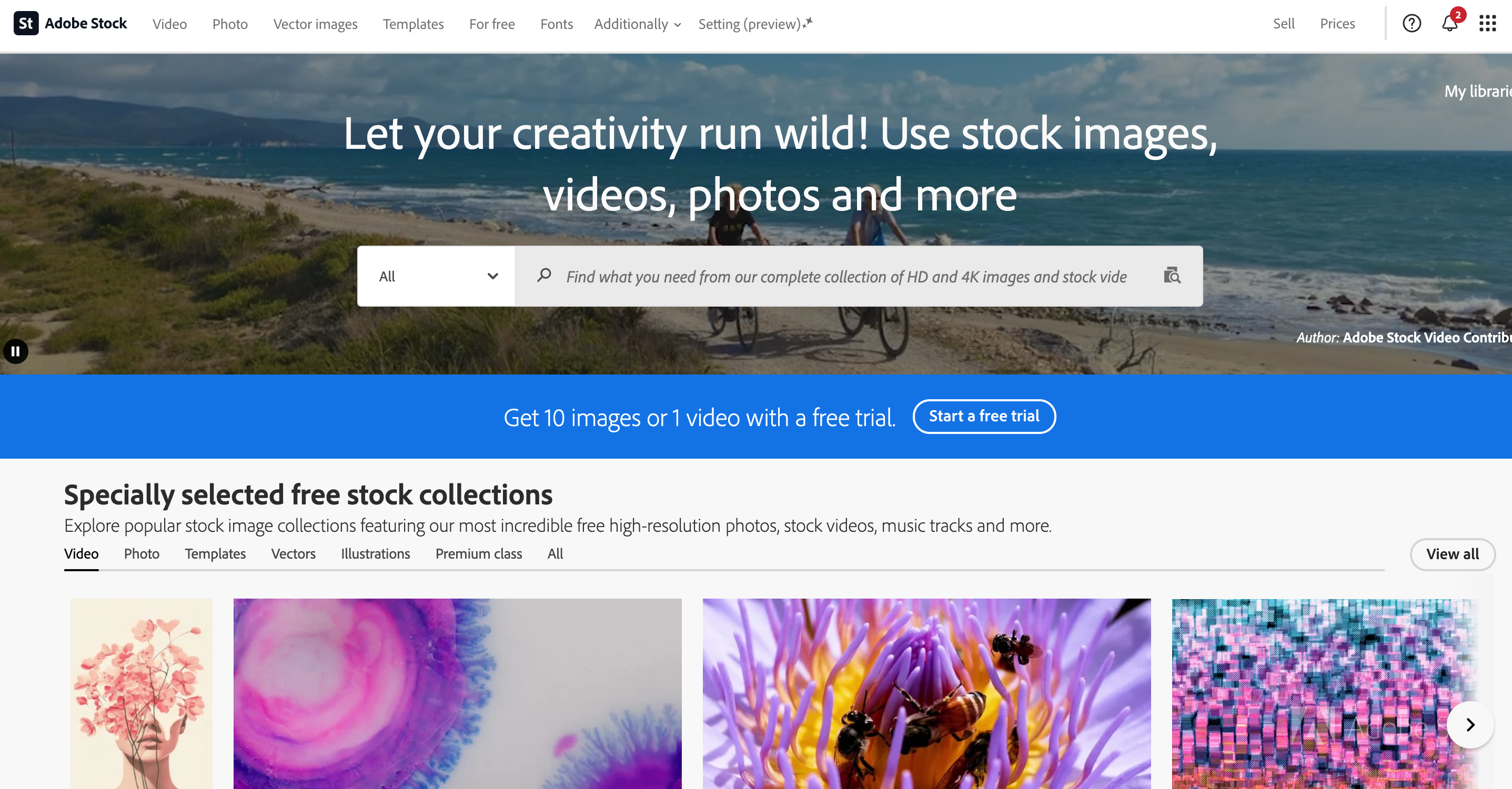

When it comes to microstocks, I work with the most well-known platforms — Shutterstock (I wrote about it here), Adobe Stock (my ode to this platform is in this post), iStock, Depositphotos, Dreamstime, 123RF, and Pond5. Each one has its own quirks: some have more lenient moderation, others pay out faster, and some have buyers who value an unusual perspective.

But microstocks, while being the flagship of the image-selling world, isn’t the only category out there. There’s also what’s called midstock. Let’s see what that’s all about.

Midstock: A Space for an Author’s Voice

Midstock is a completely different world. Here, things are less about mass volume and much more about valuing a personal touch. If microstock is the supermarket, midstock is the cozy, atmospheric bookstore where the owner knows every regular customer by name.

Images here sell for higher prices — anywhere from $10 to $50. Buyers often come looking for uniqueness. They want not just a picture but a mood, a story, a detail they won’t find on every billboard. Competition is lower, and the satisfaction of a sale is often greater — because they’re buying your work, not just another mass-market image.

Among the midstock agencies I’d mention Photocase, Stocksy, Westend61, Cavan, and Picturepantry. Each has its own strengths: Stocksy, for example, works like an art cooperative where only select photographers are accepted, while Arcangel is a goldmine for those who love creating atmospheric images for book covers or movie posters.

Macrostock: The Summit Where Exclusivity Reigns

Macrostock is the elite level. Here, what’s sold is not just a picture but the rights to a truly unique image. Imagine a client buying not “a file,” but the right to be the only one to use it.

These platforms operate with rights-managed licenses: the terms define where, how, and for how long the image can be used. As for royalties? Hundreds, sometimes thousands of dollars. But the entry bar is very high — contributor selection is strict, and quality requirements are non-negotiable.

I know photographers who work with Getty Images, Magnum Photos, Trevillion Images, Plainpicture, and Gallery Stock. They don’t have hundreds of sales a month, but each deal is a serious amount of money and a prestigious publication.

Choosing Your Step on the Ladder

In my view, it’s best to start with microstock. It gives you experience, discipline, and teaches you how to plan your work. Once you feel confident and realize your work can stand out, it’s worth trying midstock. Macrostock, though, is a game for those ready to spend months on a single series to sell it for a truly high price.

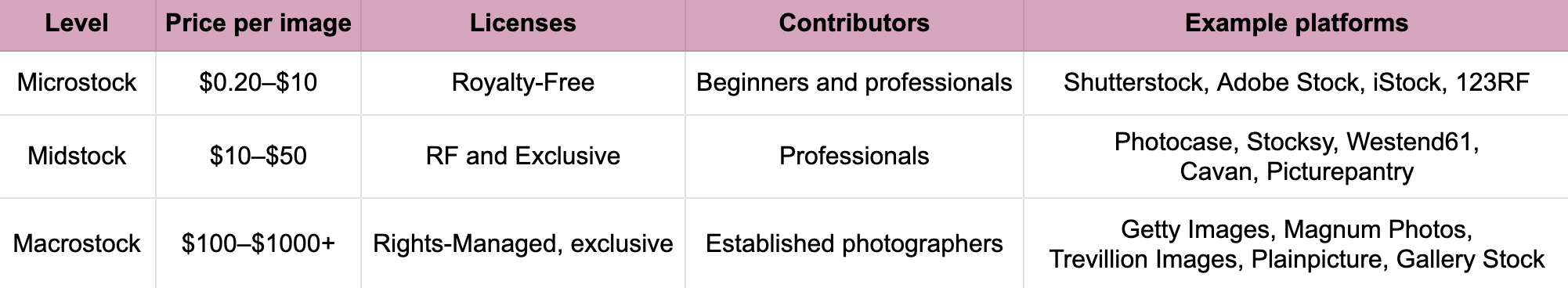

In this table, I present a brief comparison of these three types of stock photography platforms:

Many photographers work across all three levels. I tried it too — shooting for small photostocks and attempting to upload to midstock. Unfortunately, I just didn’t have enough time for both.

Midstock and macrostock require unique content, which means you have to shoot separately for those platforms, and you can’t use that same content elsewhere. In that sense, microstock is much more democratic. On top of that, the vast majority of “elite” stock agencies don’t allow AI-generated content — and for me right now, that’s a priority.

That’s why at the moment I’m focused entirely on microstock photography and videography, though I don’t rule out that one day I might want to climb one or even two steps higher.

Leave a Reply

Copyright © 2025 TagWithAi

No comments yet.